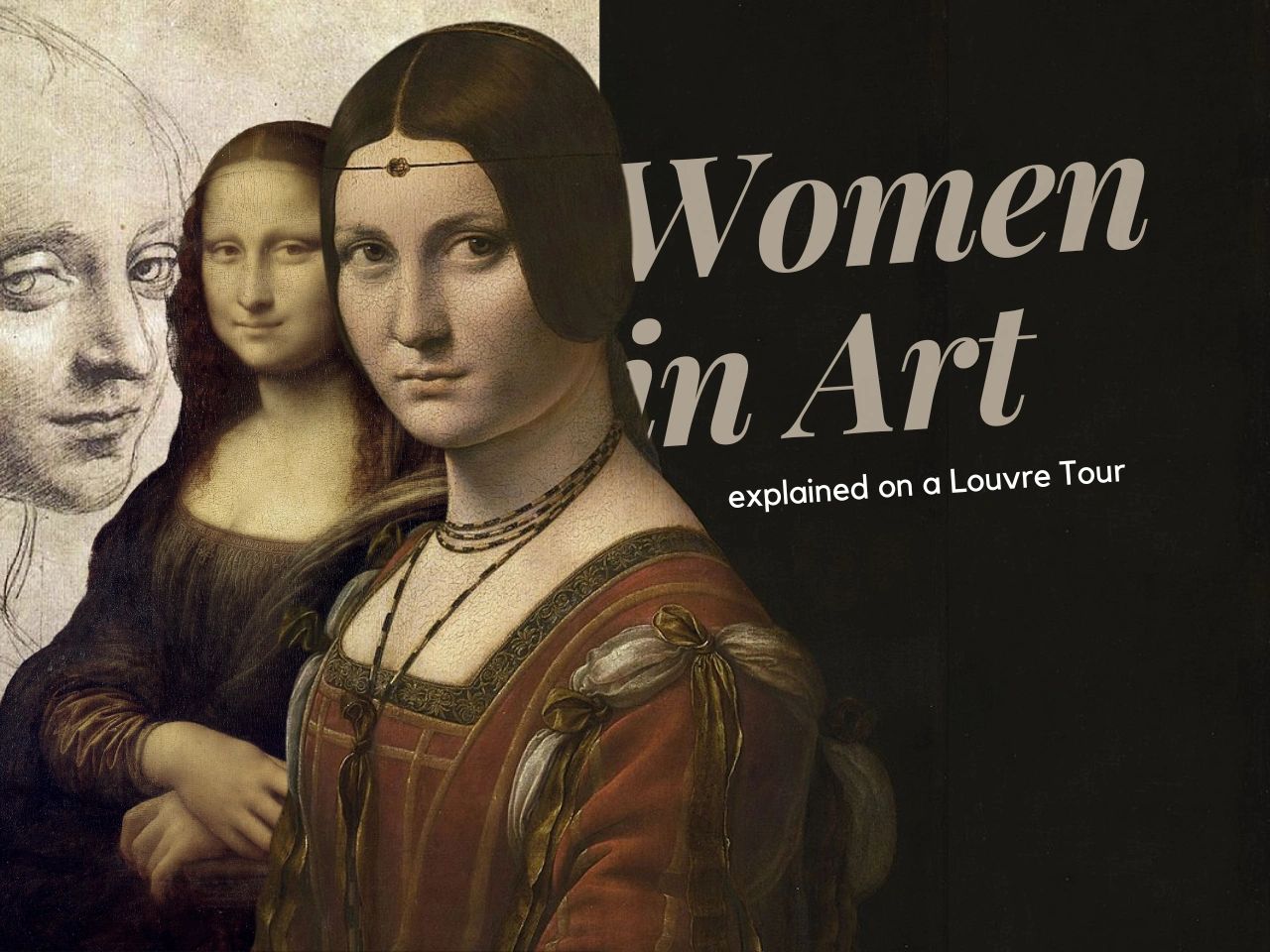

Themed tour about Women in Art - 3 hours - Louvre Museum

Women in the Louvre

Discover the unique place of Women in Art as Subjects and as Artists, through a collection of paintings, sculptures, poses and gazes. Learn about their fascinating stories during an advanced guided tour in the Louvre Museum.

Why choose the Louvre for this Art tour?

"We are not born Woman. We become Woman"

According to Simone de Beauvoir, a French Philosopher, Woman is a construct concept, through ages, societies and environment.

Nothing better than Art History to showcase these different constructs. The Louvre is a great place to come to understand the image of women in art. We will be travelling through Time and Geography to see women as artists and as subjects of artworks.

Details about our guided tour:

The Women in Art of the Louvre is a museum walking presentation about Women in Art.

*This is not based on my personal opinion nor an oriented talk.

Our women tour is based on factual information from my Société Studies class in La Sorbonne University. We enriched the tour with a journalistic research and the Louvre classes during 2022.

We are solely motivated by our passion for the Art History of the Louvre. It is possible to have a talk and ask me questions as we roam in the best Museum in the World.

As a licensed guide Conférencière, I will use my research and presentation skills, in fluent English to summarize all the dense knowledge that the Louvre and the Sorbonne taught me during five years of studies and more than 10 years of work experience.

We will speak about each Art piece representing women and read how they are represented : Symbols, model, context, material, technique, etc.

I will show you why they are exceptional.

We will talk about the three famous women Artists of the Louvre : Vigée Le Brun (1755 - 1842), Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749 - 1803), Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744 - 1818).

We could speak of the amazing artists : Rosa Bonheur as well as Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757) but it means we have to go to the dept of Drawings of the Louvre.

When we begin to explore all the many ways that women express themselves and are depicted by others, we can see how their roles change throughout time and space. We also see an all important element of our human condition.

This presentation is always helpful for visitors wanting to acquire factual information about Women in Art.

During our women tour, we can stop for a break, sit and talk, take notes or take pictures on our well-prepared itinerary.

As a major in Art History, I will also present to you my findings about my selection of Antiquity Art : Etruscan (today Italy) Mesopotamia (today Irak/Iran), Ancient Egyptians and the Roman mythology.

If you have any preference for Egyptian Women or Mesopotamian period or Roman & Greek sculptures, if you want a great expertise on a topic, I can orient you to two of our experts. They will be trained on the women tour with a strong background on Egypt or Greece, depending on your choice.

The advantage of a licensed guide is that you will be getting all these facts and findings in a form of a nice walking tour inside the museum away from the crowd.

We will skip the Line.

I will guide you through the maze effortlessly, taking shortcuts and elevators to see the Red rooms, to French paintings, to Egypt department, the Marly & Puget courtyards, the Italian Renaissance gallery, the Dutch painting and its beautiful Medici's Gallery.

We have an example of a classic itinerary for the women tour. My role is also to help you see what you want to see and customize it by email or by phone before the tour.

You may want to see the powerful women Art, or the most beautiful paintings and sculptures of women? maybe a selection of Art with a complex idea for your personal or professional projet? Let me know by email and I will help you.

Connect with Flora

Below, I will present to you some elements of our reasearch about women in art and women artists.

There will be more details during the women tours.

We can adapt an itinerary to build a unique tour just for you. When you are ready, send me an email to build the tour together.

If you are curious to see more works with live & factual explanations, you can send me an email with your exact needs.

I am a certified tour guide. I create themed visits in the Louvre with my team of certified tour guides. The Louvre contains many stories within it. You can trace so many interesting histories through its enormous collection. Some of these can be specific to an artist, a movement, a historical period, or a region.

Mesopotamia : Statue of Napir-Asu

The love between a King and Queen

Our research begins long ago, centered on the love between a King and Queen.

From around 3200 to 539 BCE, in the southwest of modern-day Iran, reigned the Elam civilization.

They were one of the earliest known groups to produce written records, and their long history beside the likes of Sumer and Babylonia show their incredible strength.

The Louvre gives us a chance to see their great metal-working ability with the Statue of Napir-Asu.

This is the largest bronze sculpture ever known from Elam, and it depicts Queen Napir-Asu, wife of King Untash-Napirisha. Her husband likely had this made as tribute to his wife.

The mysteries of the statue

The imposing sculpture weighs nearly two tons ! and that’s in its fragmentary state, the complete work was likely much heavier.

And to make it even more fearful, it contains a curse. In Elamite cuneiform, engraved on the body of the queen, reads these terrifying words:

I, Napir-Asu, wife of Untash-Napirisha. He who would seize my statue, who would smash it, who would destroy its inscription, who would erase my name, may he be smitten by the curse of Napirisha, of Kiririsha, and of Inshushinak, that his name shall become extinct, that his offspring be barren, that the forces of Beltiya, the great goddess, shall sweep down on him. This is Napir-Asu's offering.

Strangely, the exterior is copper while the inside was filled with bronze, which would have been much more valuable in Elam at the time. While the sculpture likely had valuable metals inlaid on the surface, it is odd that so much precious material would be committed to the inside.

We still do not know if this a romantic detail? A statement about the value of the Queen’s soul? A vulgar display of wealth? Just an Art technique? We will likely never know.

the Spouses from the Etruscans

Women in the Etruscan Civilization

Through the 8th to 3rd centuries BCE, the Etruscan civilization thrived in central Italy. In many ways, they set the groundwork for the Romans to follow, and they greatly influenced Greek culture.

One of their most striking features, being an ancient Mediterranean civilization, is the role of women.

Unlike many of their contemporaries in the area, Etruscan women enjoyed a high level of equality:

This can be seen in the shared focus of the mother’s and father’s lines on tombs, female access to literacy, and their presence in public life.

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses

This fact is immortalized in the Sarcophagus of the Spouses housed at the Louvre.

Made sometime around 520 BCE, it depicts a married couple reclining together, enjoying a feast.

The balanced emphasis on the husband and wife is common in Etruscan art, but not in similar pieces from Rome or Greece.

Greek and Roman Women

The fiction does not match reality

As mentioned above, women in Rome and Greece had to survive in highly patriarchal societies.

The rights of women fell far behind their male counterparts. This extremely sexist society barred women from political agency and even from owning land.

In Greece, married women of the upper classes wouldn’t even be able to leave the house unaccompanied.

Despite this terrible treatment of women, both Greece and Rome also gave us many triumphant depictions of female goddesses.

This dichotomy has been explored in great detail by critics, but when you actually stand in witness to the awe-inspiring statuary showing women as icons of power — it strikes you all over again.

The same civilizations that gave us the likes of The Winged Victory of Samothrace, Venus de Milo, and Diana the Huntress resisted giving women any level of equality in society.

1 - The Winged Victory of Samothrace

This stunning statue of Nike, the goddess of victory, stands above the main staircase in the Louvre, overlooking all who come through its doors.

It is quite a sight to see, showing the female form not as an object of desire but one of power.

Made around 200 BCE, the statue was created as an offering to the goddess. It is recognized as one of the greatest surviving works from the period, and it still makes an impact today.

2 - The Venus of Milo

Masterpieces from ancient Greece, the Venus (Venus de Milo, Venus of Arles) show us the female deity of Beauty and Love with an almost geometric face and a perfect spiral figure.

The Venus de Milo was sculpted near the end of the 2nd century. When it was brought to the Louvre in 1820, it quickly gained a following in Europe as one of the best examples of Hellenistic art — in part due to a promotional campaign by the French government.

Many statues survive from ancient Greece and Rome. I can show where too look in a statue to finally understand why they are unique and preserved in the Louvre today.

The Model for Venus of Arles, was so beautiful that she was sued for profanity. For her defense, her lawyer showed her naked body to the Judges. Once they have seen her perfect beautiful body, they instantly freed her.

In Greece, the search for the perfect beauty has gone too far. One artist in the Louvre invited all women from Greece and select the five most beautiful women, in order to construct Helen of Troy, also know for her Ideal Beauty.

Many statues survive from ancient Greece and Rome.

I can show where too look in a statue to finally understand why they are unique and preserved in the Louvre today.

Movement, Light and Beauty

The Greek, Roman and French sculptures are highly detailed and precise. Thus, they will be very helpful for us to understand during the tour the traits of what is considered beautiful and how did they evolve as we walk in the Greek Roman Sculptures dept.

We will separate the Greek myths from the truths (what is sculpted exactly and what we understand today) about the beauty of women.

Zeuxis and the Search for the Ideal Beauty

In Greece, the search for the perfect beauty of Helen of Troy has gone too far.

One artist in the Louvre depicted the painter Zeuxis in charge of painting Helen of Troy. His idea was to invite all women in his studio and select the five most beautiful models, in order to construct Helen of Troy, out of these five.

3 - Diana of Versailles

This Roman statue from the 1st or 2nd century CE of the huntress goddess Diana is an unbelievably complete copy of an earlier Greek statue (made sometime around 325 BCE).

It shows the huntress reaching for an arrow from her quiver, confident and poised. A leaping deer acts as her familiar.

Again, it reminds us of the troubling difference between the portrayal of women in art and the reality of their lives in Roman society.

Here, a female goddess is shown as a capable character ready to strike — an image that arises out of the imagination of an artist living at a time when women knew great hardship and limitation based on their sex.

cleopatra at the Louvre

Cleopatra VII Philopator

Ancient Egypt presents us yet another series of questions: We can find a female pharaoh with a beard, a masculine sign, attribute for wisdom. Another female Pharaoh depicted as Isis herself!

After Egypt was conquered by the Greeks in 305 BCE, they were ruled by the Ptolemaic Kingdom. The culture saw a merging of Greek and Egyptian sculpture, leading to many exquisite pieces.

The views of women would certainly not be considered modern by any stretch of the imagination. But that’s not to say that women did not rise to the heights of power, with there even being female Pharaohs.

Cleopatra VII Philopator is one of the most well known among them.

At the Louvre, you can see a stele showing Cleopatra VII giving offerings to Isis, a central goddess in the Egyptian pantheon.

There is also a bust of a female pharaoh, likely Cleopatra VII, who is depicted as Isis herself.

These are artifacts from a culture that had limited roles for women but would still follow a queen — though one not given the same level of trust in administration as a male would experience.

* On our Egypt dept tour, we can dive into the lives of Egyptian women, their relationship to men, the social equality and balance in Egypt, but also into their intimacy, their dress code, perfumes, jewelry... and a quick overview of their evolution during the three main periods of Egypt civilization.

Women of the high Renaissance in the Louvre

Mona Lisa - 1503

With the rise of the Renaissance in Italy, painters were pushing the boundaries of realism on the canvas through innovative new techniques.

They were also exploring new ideas. It is at this time that we find Leonardo da Vinci, among the greatest to ever pick up a brush. His masterpiece Mona Lisa (c. 1503 - 1506) is a transcendent work that has gone on to become the most well known painting in the world.

The female subject looks directly at the viewer, something vanishingly rare for the time. She is also given a great depth of character, with a facial expression that has puzzled and engaged viewers for centuries.

Leonardo painted Mona Lisa with all the projected power that artists had reserved for elite males in society. But here, we see a woman this way — giving us a hint of changes to come much later.

Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at Her Bath - 1654

Rembrandt (1606 - 1669), master of the Dutch Golden Age, gave us this gorgeous painting in 1654. It shows us a moment from a story in the Old Testament. King David glimpsed Bathsheba bathing, and though she was married to a general, he called on her to visit him. Their adulterous affair led to David sending her husband off to certain death in battle. In the end, Bathsheba became an outcast after her child with the king was stillborn.

In the painting, Bathsheba holds the letter from David, no doubt calling on her to visit the king for an illicit rendezvous. While Bathsheba does not know what is going to happen, Rembrandt gives her an emotional depth and pain that tells us two things. One, that she is likely very unhappy in her current life. And two, that she is destined for a tragic end.

Plenty of European painters had lavished a tremendous amount of detail on nude female bodies before and after Rembrandt. But in this painting, the true narrative takes place entirely through facial expression. It is an exploration of a human being whose life is about to be completely upended. We see her nudity much the same way she sees it — a matter of practicality for bathing. In this way, we are invited to see the world through her eyes, not David’s.

At the same time, Rembrandt does not desexualize Bathsheba. Instead, he strikes a balance.

We see the same rapturous beauty that David saw from his terrace, but emotionally, we take on her point of view. This subtlety makes it a major turning point for the depiction of women in European art.

Women of the Romantic era

Liberty Leading the People - 1830

By the 19th century, women were still not seen as equals in Europe, though painting often used female subjects.

Leading romantic Eugène Delacroix (1798 - 1863) created what is considered his magnum opus in 1830. In Liberty Leading the People, the ideal of liberty is not a man but a woman. She charges onward over the casualties of war, holding aloft the tricolor flag of the Republic.

Much as the ancient Greeks used the female form to personify victory, Delacroix relies on a female subject to embody the philosophy and drive of the July Revolution, which deposed King Charles X.

But Liberty is not presented as a completely unreal goddess. Instead, she is given a hearty realness, making her as much a woman of the lower classes as an embodiment of a concept. This approach gives the painting far more weight — both visually and emotionally. By making Liberty a full human being, we are much more committed to the drama of the scene.

Behind her is a class coalition of bourgeois, student, and proletarian soldiers, and they rally around Liberty as their leader. This active role for a woman, especially in a battle scene, was almost unheard of up until this point, but it would become much less rare in generations to come.

The Toilette of Esther - Chasseriau 1841

One of Delacroix’s disciples, however, shows us that progress is not linear. Théodore Chassériau (1819 - 1856) painted The Toilette of Esther in 1841.

More than a decade after Liberty Leading the People, the painter gave us an image from the Old Testament’s Book of Esther.

But rather than showing her with a well rounded humanity, she is used as an excuse to create a painting in the orientalist style.

The Valpinçon Bather - Ingres 1808

Here, the influence of Chassériau’s teacher Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780 - 1867) can be felt alongside the growing affinity for Delacroix.

Ingres loved orientalist scenes — paintings that depict “the East” as a foreign, unknowable, and mysterious region.

The Turkish Bath 1863 - Ingres 1863

Ingres’s own The Turkish Bath (1863) was still a ways off from being released, but it is perhaps the most famous example of this exaggerated tradition. It is not only culturally exploitative, but orientalist paintings are often also highly exploitative of women’s bodies.

The Toilette of Esther and The Turkish Bath are essentially excuses to provocatively show the women body forms and a mean to beautify the paintings.

The beauty of Mary Magdalene

The orientalists were predominantly focused on the erotic side of beauty, but all kinds of beauty can be found at the Louvre.

When we focus on the way specifically feminine beauty is portrayed, we see the changing pressures and demands made on women through time as well as the celebration of the female form.

The beautiful German Lady of Erhart:

Gregor Erhart’s Saint Mary Magdalene (c. 1515 - 1520) is a wooden sculpture that gives an intimate look at this early follower of Jesus Christ. Her fantastically long hair provides a great deal of movement to an otherwise still moment of introspection. Mary Magdalene is shown caught in a reverie, a thought, a day dream, a moment of grief. With every detail, Erhart emphasizes the beauty of the Saint.

The bust of Marie Antoinette:

The feminine ideal keeps changing as you move through the Louvre’s timeline. Once you get to the late 18th century, as with Louis-Simon Boizot (1743 - 1809) and his Bust of Marie Antoinette (1781), we see elaborate fashion project beauty and standing.

Symbolic beauty of Women

The two women figures of Mary Magdaene and Mary Antoinette were both considered as very attractive and appealing to men artists (and kings!) but these two figures could not be more different :

1 - One is a Biblical figure whose low social position and poverty put her on the path to grace.

2 - For the other, her radiant beauty and wealth took her to the top rank of French society.

and this dichotomy plays itself out across all the many ways that predominantly male artists have depicted women through history.

women artists at the Louvre

1700 - 1850 Talented women artists in front of the male dominated academy

It is during the late 18th and 19th century that women in Europe began to gain more access to the world of art. And the emergence of talented women artists allowed them to show viewers life from their own point of view.

While we often think of the struggle for gender equality mostly playing out at the end of the 19th and through the 20th century, a lot of groundwork had already been laid by women pioneering their own paths through the French Royal Academy.

The Academy and Salon system of France had restrictions against female participation, and this greatly reduced the amount of their art shown to the public.

There were no doubt plenty of women masters, but their work was never given the same notoriety in society — purely on the grounds of sex.

Nevertheless, many persevered and gave us works of lasting importance:

1 - Anne Vallayer-Coster

Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744 - 1818) was a well respected artist in her time. This is despite her being forcibly relegated to the still life.

At the time, still life painting was not seen as holding the same value as other kinds, like religious and historical paintings. But many genres considered prestigious required nude models, and the mores of 18th century France prohibited women artists from this practice.

Rather than be deterred, Vallayer-Coster dove in headfirst, bringing the still life to levels of realism and drama never seen before. Her 1769 painting Attributes of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture shows her otherworldly technical mastery, as well as her ability to create quiet yet compelling images that contain intellectual and aesthetic delights.

In Still Life with Tuft of Marine Plants, Shells and Corals (1769), you can see her extraordinary attention to detail, texture, composition, and color. It is deeply moving and dense with emotional content, something no artist had been able to do in the genre. The exotic shapes of aquatic life also lend a startling charisma.

The Louvre honored her and shed the light on her painting of Still Life with Tuft of Marine Plants, Shells and Corals during an amazing art exhibit about Things in Still Life - "Les Choses" - Although it is crowded, you can get close to many amazing works until Jan 23, 2023.

2 - Adélaïde Labille-Guiard

Another one of the first women to enter the Royal Academy was Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749 - 1803). Her portraits and miniature paintings deliver a lively sense of the people depicted.

She encouraged the women she painted to look at the viewer, something very unusual in the 18th century (and reminding us of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa). This allows us to form a much deeper connection to the subject. It also gave Labille-Guiard an opportunity to make a subtle statement about the role of women.

While she was extremely accomplished in her day, we know very little about her education. This is because male artists were strongly discouraged from teaching women. It is likely that her mentor was not made public to protect his reputation.

Pastel masterpiece by Adélaïde

Pastels are a dry technique, easy to learn compared to paintings and it was left to women mostly. But, here, you can see her great portraiture at the Louvre of the Painter François-André Vincent (1795) as if his expressions are telling us something about his personality.

Though this does not rise to the heights of a work like Self-Portrait with Two Pupils (1785), it gives a hint of the brilliance that Adélaïde Labille-Guiard fought to share with the world.

3 - Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Artist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755 - 1842) earned notoriety through her extensive portraits of the French nobility. Her nearly one thousand surviving paintings now appear in museums around the world, a fitting tribute to the legacy of this artist.

She made her reputation by working extensively with none other than Marie Antoinette. This connection helped bolster Vigée Le Brun’s profile and secure new clients such the Emperor of Russia.

First painting of a feminine gaze

As a portrait artist, her strength lies in balancing likeness with glamor.

Though she reached the heights of celebrity near the end of the 18th century, her deep connection to royalty forced her to flee during the French Revolution.

Self-Portrait with Daughter Julie (1786) is a tender look into the life of the artist and her daughter. The warmth between them, and the way Vigée Le Brun captures the magic of childhood, make this remarkable piece shine

Laurence des Cars - Head of the Louvre - since 2021

Much of art history, particularly in Europe, is dominated by males. But as things have progressed, women are now an integral part — from leading artists to, now, Director of the Louvre.

Laurence des Cars became the first female director of this legendary museum in September 2021 and made many changes ever since, mostly on the exhibits, the flow of visitors, and the reputation of the Louvre on the global Art scene.

Highly decorated and truly respected woman at the cockpit of the biggest museum, it’s a sign of just how far the world has come.

We began with the sculpture of a queen and worked our way through thousands of years of women as both the subjects and creators of art. We have finally arrived at a time when women stand in one of the most powerful positions in the art world. It is not unlike ascending the Louvre’s main stairway to greet the goddess of victory herself, arms spread to invite us all into a more equal future.

This tour is made possible thanks to the Louvre curators and the Historians who helped me in my research.

If you are looking for an in-depth tour that can explore this fascinating topic, you’re at the right place. Our women-led team of tour guides can build your perfect Louvre experience. All you need to do is reach out today!

Our women-lead team : Louvre guide

Flora G. and a painting of Ingres

Private Guided tours in Paris Museums

- Louvre tour guide

- Louvre Highlights

- Louvre Full Tour

- Louvre by Night

- Louvre and D'Orsay Combo

- D'Orsay guided tour

- Musée L'Orangerie tour

- Book a Louvre guided tour

- Themed Tours

- Limited Tours

- Bible Louvre private tour

- Egypt Louvre guided tour

- Queen Medicis by Rubens

- Women in the Louvre

- Women at the Orsay Museum

- History and Art of Paris

- Art and Power Napoleon

- Eastern Arts Louvre Paris

- Apollo Gallery

- Male Gaze

- impressionism

- Louvre Museography

- How to Buy Tickets Louvre

- Louvre access and info

- How to Go to the Louvre ?

- Hidden masterpieces

- Louvre with kids

- Treasure hunt for kids

- Budding Artist Orsay

- Sarcophagus of Spouses

- Art History in Paris

- Louvre History

- Legal & Data Privacy

- Flore Gurrey

TOUR GUIDE PARIS

Cookie Policy

By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of Google Analytics