Quick detour to see Eastern Arts at the Louvre Museum

Arts from the east

The Louvre is a world-class art museum.

And to have a historic collection with universal appeal means showing artwork from all cultures.

One of the most beloved of these is the Arabesque decorative arts.

Islamic arts department at the Louvre

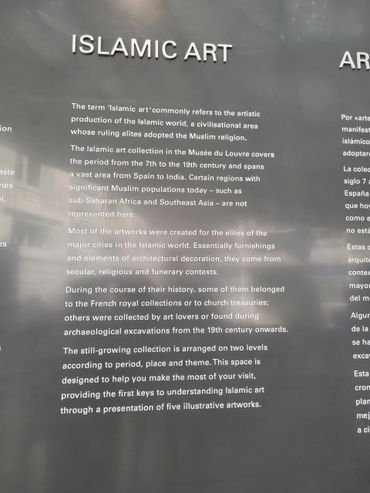

What Is Islamic Art?

If you’ve visited the Louvre Abu Dhabi, you’ve no doubt seen the in-depth curation and Islamic art expertise that the Louvre staff brings to the table.

The incredible works you can see from the Islamic world at the Louvre in Paris are frequently the most enjoyable for visitors. With so much gorgeous art spanning so much history in the tradition, it’s easy to see why.

Islamic art refers to work created both for the worship of the Muslim faith and that created in Muslim cultures and/or by Muslim artists.

The rise of Islam in the Middle East not only brought with it a new religion, but also a new way of organizing society. This created unique cultural conditions, giving rise to art forms, techniques, and styles never before seen.

Because of the breakthroughs in science and the humanities during the Islamic Golden Age (8th century to the 14th century), there were many artistic inventions that first appeared in this field. That gives Islamic art a long history of development, further adding to their intrigue and splendor.

Preparations

If you want a guided tour of the Louvre focused on the world of Islamic art, you’ve come to the right place. We create special tours with experts who can shed light on the historical and artistic context of the work you see. So contact us today and start planning your ultimate Louvre tour!

But before you get your plane tickets, let’s do a deep dive on Islamic art at the Louvre. We’ll find out what are the essential features of this work and what makes it so special in world history. We’ll even take a peek at some examples pulled directly from the collection.

The history behind the art works

The beginnings

Islamic art initially borrowed heavily from Greco-Roman, Byzantine, and Sasanian influences.

And due to the wide geographic spread of Islam over time, more and more influences came to be represented. But eventually, certain tell-tale characteristics did begin to emerge.

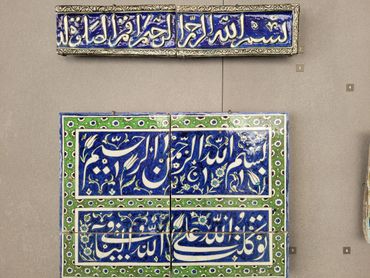

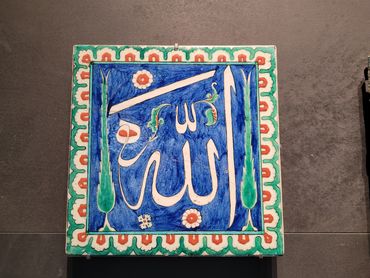

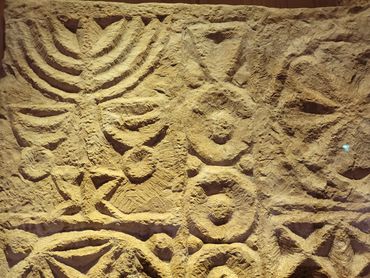

One of the most striking is the intricate detail in surface decoration. These frequently use plant forms combined with motifs of calligraphy and abstract geometrical patterns. In painting, pottery, textiles, and architecture, artists have explored these features extensively.

Figurative work featuring depictions of humans and animals does exist in Islamic art.

However, many areas where the religion and culture spread consider this a form of idolatry, and so there has been a consistent push in many areas to focus on the abstract (though, contrary to popular belief, depicting humans and animals is not explicitly prohibited in the Quran).

For this reason, Islamic art is one of the earliest examples of an extensive, well developed sense of abstract art.

The caligraphy

Another major influence it has had is on the beautification of writing as an art unto itself. Due to Islam’s focus on the written word — both in holy scripture and in its pursuit of a unified code of laws and extensive literature — calligraphy has been an important element of visual art. Much of modern, international graphic design is essentially rooted in this field.

Why do we love this Art?

From the dizzying beauty of arabesque designs to the stunning grandeur of mosque architecture, Islamic art has provided the world with one of the most prosperous flowerings of creative expression.

One of its strengths is the wide diversity of influences combined with the unifying cultural, philosophical, and religious guidance of Islam. After its rapid spread around the globe, the religion has become one of the largest in human history. In only a century, Islam expanded from the Arabian peninsula all the way to the Atlantic Ocean and Central Asia.

This has brought together a wide range of people into discussion. And in art, this is particularly true. The spread of Islam made the Arabian peninsula a key crossroads of civilization, a place where creatives synthesized a tremendous amount of cultures into a unified artistic vision.

The resulting balance between eclecticism and unity has created some of the most beautiful works ever witnessed in architecture, the decorative arts, and fine arts. These achievements have captured the imagination of countless generations in the West and East.

The Influence of Oriental Art on Europe

While Islamic art on its own is a deep well of masterpieces, it has also been an enormous influence on the rest of the world. It has helped to inspire new movements that have changed art history in several continents.

This is especially true for the Italian Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci. The polymath was inspired by the Arabic intellectuals he read. These were people who pursued science, engineering, architecture, art, and philosophy. Leonardo took this as an example of how to live.

From the Islamic world’s scientists, he learned the latest insights in optics, the behavior of light, and the perception of light and shadows. This study allowed him to gain a greater understanding of how human anatomy turned light into images — useful both for understanding human sight as well as how to paint more realistic work.

Leonardo was especially inspired by Ibn al-Haytham, the father of modern optics. This influence is shared by the likes of Galileo Galilei, René Descartes, and Johannes Kepler.

a mix of cultures, Arts, and Science

The technological innovations of Islamic art also had direct impacts on ceramics, textiles, architecture, photography, metalworking, music, and more.

Aesthetically, Islamic art changed the decorative arts in the West completely. It also provided a basis for abstract artists in the 20th century to draw from, as well as an inspiring example of creative vegetal forms that would help develop the Art Nouveau movement.

The Louvre’s Islamic Art Collection

While there are countless items in the "Arts de l’Islam" section of the Louvre, we only have space to go into a couple of Works:

- Poetic Joust’ Panel

- Baptistère de Saint Louis

These only glimpse the full range of the collection, but they stand as truly great works that demand to be seen in person.

Poetic Joust’ Panel

This work is made out of 63 ceramic tiles — a wall feature that was once presented in a palace. It originated in the 17th century, in what is modern day Iran, and it has since traveled the world to live at the Louvre where it continues to delight visitors to this day.

The panel depicts a scene in an extravagantly rendered garden, where one poet composes his verses and another reads them aloud, with two standing to the sides as an audience. It is no doubt a joust using words — like a centuries old rap battle.

During the Louvre by night, the colors are extraordinarily vibrant: allowing the design to overawe the viewer with its exquisiteness, much like a lovingly tended, royal garden would. The textiles that the four characters wear continue the flowery imagery. If you squint, you can see that the entire surface of the panel is really a chance for blossoms to be shown in all their magnificence. Here, the natural world is interwoven with human enjoyment, expressing an effortless joy of being on earth.

The subject matter also gives us insight into the cultural values of language and the power of the word. This is a “joust” where the combatants are using their writing, recalling the old adage about the pen, the sword, and which of the two is mightier.

Baptistère de Saint Louis

This 14th century masterpiece was created by Muhammad ibn al-Zayn, a coppersmith who hammered and engraved the vessel before inlaying brass, gold, and silver on the surface in intricate patterns.

Though it is a stunning work, we don’t really know what it was originally made for:

It first appears in the historical record as part of a church inventory in France, far from the Levant where it was created.

It was later used as a baptismal font for successors to the throne — the highest honor the French could give a vessel.

For this reason, it unites the two worlds of France to the West and the Islamic lands to the East.

A hidden Masterpiece

The exterior contains four medallions and four bands featuring twenty-four characters, including four on horseback. The illustrated scenes are complex and evocative of a narrative. The images continue on the inside as well.

When you see it in person, the fine details are absolutely breathtaking. It is an unbelievable work of subtlety and mastery, exalted through the use of precious materials. It really is a vessel fit to baptize a future king.

Visit the Louvre with a tour guide

If u I If you eou want to see all the incredible Islamic art waiting for you at the Louvre?

Contact Flora with a simple email, and we can begin creating your special tour of this French museum with a global perspective.

If you need a tour in Hebrew or in Arabic, contact us. For more tours in Arabic of the Arts of Islam : We reccomend our Guide MATAHAFI.

The expansive collection of work gives you endless artifacts and art to see and discuss, all with the guidance of an expert who can tell you all you need to know. This is the best way to see Islamic art at the Louvre.

more works from the East

Art exhibits

The Eastern Arts Department of the Louvre puts on display few temporary exhibits that we will cover together.

If you are interested in our themed tours or exhibits tour, you can start planning the custom-made tour with Flora.

Uzbekistan’s oases

Visiting the Splendors of Uzbekistan’s Oases

The Splendors of Uzbekistan’s Oases is a recent Louvre exhibition that tells the story of the land that sat at the beating heart of the Silk Road. You can almost smell the spices and hear the eclectic range of music and languages that drifted through the streets of the ancient cities built in Uzbekistan’s oases.

Running from 23 November 2022 to 6 March 2023, this show delivered a fascinating look at art from Uzbekistan — a land that served as the crossroads of the world for almost 2000 years. The Louvre exhibit brings together the museum’s commitment to honoring Eastern art as well as its world-class curation team.

Using 170 works of extreme historical value and artistic merit, Uzbek art history is revealed across a wide range of mediums.

The exhibition was spearheaded by president of Musée Guimet Yannick Lintz and Rocco Rante, the Louvre’s archaeologist in the Department of Islamic Art. Rocco has been active on digs near Bukhara for almost 15 years. Together in partnership with the Uzbekistan government, they were able to bring us a feast of Central Asian art during one of the most crucial eras in human history.

Why Uzbekistan Is So Important

The legendary Silk Road

Many people living today in the West are not aware of how vitally important Uzbekistan culture was, is, and continues to be. Though it is landlocked, it lies in a vital point between East and West, in what is called Central Asia.

It is here that the famous caravan routes known as the legendary Silk Road converged for so many centuries. That made Uzbekistan a truly cosmopolitan culture at a time when that was incredibly rare. It benefited from a wide range of trade goods, ideas, and beliefs. In that soup of culture, great art is made.

A Brief History of Uzbekistan

The Louvre exhibit begins with Alexander the Great’s conquest of the area in the 3rd century BCE. But the area he conquered was already cultivated, with widespread irrigation and urban development.

The major population centers were thriving, as China was already engaged in trade with Europe. Those routes cut right through Uzbekistan — meaning there was plenty of wealth splashing around the desert.

Cities like Bukhara and Samarkand benefited from both the excess wealth and diversity of cultural influences the Silk Road brought them. That is why, by the time Alexander’s army arrived, he found the territory difficult to conquer and impossible to maintain power over.

Various Persian empires laid claim to the area for centuries. The entire time, Greek, Iranian, Indian, and Chinese culture mixed with local traditions to form a highly fluid and exciting atmosphere, one that produced endlessly fascinating works of art.

Major shifts occurred with the introduction Islam in the 7th century and the invasion by Genghis Khan in the 13th. As Mongol rule waned, Timur (Tamerlane) was able to conquer the area near the end of the 14th century. It is during this time that the region underwent the Timurid Renaissance, which upheld and radically developed advancements made during the Islamic Golden Age.

This “renaissance” slightly pre-dates the start of Italy’s, and its wonders — intellectual, architectural, and artistic — rival any similar period in Europe.

It’s important to remember that throughout these many centuries, Uzbekistan never wavered as a leading hub of international thought. And so, as we walk through the Louvre exhibition, we find ourselves encountering work that is startling for how forward thinking and yet very old it is.

The Importance of Oases

The title of the exhibition points to the oases that have been the center of urban development in the region since its earliest settlements. These spots in the desert provide water in an otherwise inhospitable climate, making them crucial for agriculture.

The cities that built up around these oases became necessary stops for traders making the long journey between Europe and China. In this way, people weren’t just drawn to the cities of Uzbekistan, they had to visit as a matter of survival. The steady stream of people from distant lands brought new languages, religions, songs, tastes, and jokes into the local scene.

This turned the cities into a different kind of oasis: a cultural one. And so these oasis cities play the backdrop for the artwork on display in the Louvre exhibition.

Why the Exhibition Matters

Thanks to funding by the Louvre and the French government, many of the pieces on display in Splendors of Uzbekistan’s Oases are newly restored using leading professionals in the field.

Because the curatorial team chose this subject matter, Uzbekistan wonders have been revived to their original power like never before. The restorations were so effective that, in some cases, never-before-seen details were brought to light.

This is the power of collaboration across borders. Audiences in Paris get to learn from the cultural wealth of Uzbekistan, while Uzbekistan enjoys the world leading restoration expertise of the Louvre. When we work together, so much is possible!

Selections from the Splendors of Uzbekistan’s Oases

To get a sense of the immaculate work at the exhibit, let’s take a short stop at some of the works of art on display.

Katta Langar Quran (8th Century)

The pages from the Katta Langar Quran are possibly the star of the show. This manuscript is believed to be one of the oldest surviving copies of the Quran in existence — making it extremely important to the Islamic faith and to our global human heritage.

It spent centuries hidden away on a mountain, but it now travels the world, bringing audiences in close proximity to these pages.

Thanks to restoration work by the Louvre and collaborators, the Katta Langar Quran is more legible than ever before. In fact, it looks shockingly new.

Painting of the Ambassadors (8th Century)

This partially surviving fresco stands today as a major part of Uzbek cultural heritage. It has become so widely known that it is a symbol of the country’s history, despite our murky understanding of its subject matter and its incomplete survival.

The work is one of the few surviving representatives of art from Sogdian culture, which was at its height at the time this piece was painted. The frescoes altogether decorated the walls of a house, and it seems to use each wall as an homage to one of the cultures that influenced the region. For instance, one wall shows scenes from China, one Samarkand, and another India.

The stunning use of color and the epic sweep of its narrative recommend this as a major work from Sogdian culture, and a rare example of its art. Even though it is in poor condition, we are lucky that we have the work at all — it was only discovered by accident thanks to a road construction project in 1965.

The frescoes enjoy such a prestigious status in its native region that some have called it the “Mona Lisa of Uzbekistan.”

Statue of Mara (7th Century)

Made of unfired clay, this striking sculpture stops visitors in their tracks. Without knowing anything about the subject matter, we are caught in the blank gaze of the eyes, transfixed and yet terrified.

This work depicts the demon Mara — alternatively called Makhakar or Mahakala — from the Buddhist tradition. As you can tell from the image, he embodies pure evil. While Buddha laid down tenets that allow us to transcend temptation and so escape suffering, Mara brings temptation to us.

He is the demon most associated with rebirth and desire, which are the very things that Buddhism teaches its adherents to avoid. In keeping with that, it is said that he personally went after Prince Siddhartha, luring him away from enlightenment with tantalizing visions.

The work comes to us from Kuva — an oasis city in the region of Fergana. It was found in a temple, where it served to warn Buddhists of the dangers and evil origin of temptation. To drive this point home, Mara wears a human skull on his head.

The Treasures of Central Asian Art

The selection above barely scratches the surface of everything the exhibition had to offer. The Splendors of Uzbekistan’s Oases brought a plethora of Uzbek art to the world’s biggest and most influential museum, which makes it a unique cultural opportunity. It continues the Louvre’s commitment to a truly international view of art.

By bringing together cultures from around the world, we are all able to learn, understand, and grow. That is the power of art, and these are themes that echo in the long history of Uzbekistan.

The Louvre takes visitors on a journey through the art of the East and the West. Its leading experts and impressive resources bring it all to life in a way no other museum in the world can!

a tour in a different language ?

Some rooms of the Louvre are closed on certain days of the week.

Please start planning ahead for a special tour of the Louvre in the best conditions.

Louvre Advanced & Themed Tours

Paris, France

Openings of the Rooms

Mon | 09:00 am – 05:00 pm | |

Tue | Closed | |

Wed | 09:00 am – 06:00 pm | |

Thu | 09:00 am – 06:00 pm | |

Fri | 09:00 am – 09:45 pm | |

Sat | 09:00 am – 06:00 pm | |

Sun | 09:00 am – 06:00 pm |

Private Guided tours in Paris Museums

- Louvre tour guide

- Louvre Highlights

- Louvre Full Tour

- Louvre by Night

- Louvre and D'Orsay Combo

- D'Orsay guided tour

- Musée L'Orangerie tour

- Book a Louvre guided tour

- Themed Tours

- Limited Tours

- Bible Louvre private tour

- Egypt Louvre guided tour

- Mesopotamia in the Louvre

- Women in the Louvre

- Women at the Orsay Museum

- Queen Medicis by Rubens

- History and Art of Paris

- Apollo Gallery

- Art and Power Napoleon

- Male Gaze

- impressionism

- Eastern Arts Louvre Paris

- Louvre Museography

- How to Buy Tickets Louvre

- Louvre access and info

- How to Go to the Louvre ?

- Hidden masterpieces

- Louvre with kids

- Treasure hunt for kids

- Budding Artist Orsay

- Sarcophagus of Spouses

- Art History in Paris

- Louvre History

- Legal & Data Privacy

- Flore Gurrey

TOUR GUIDE PARIS

Cookie Policy

By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of Google Analytics